Like a great wall extending all the way from the U.S. border in Texas, from the state of Coahuila to the state of Puebla, Mexico’s Eastern Sierra Madre captures all the moisture from the winds and clouds blowing inland from the Gulf of Mexico. It hosts a mosaic of ecosystems and species, and its latitudes, altitudes and rain patterns make it a mountain range that is more diverse, rugged, and higher in elevation than its sister range further west, the Western Sierra Madre. Seen from the air, it is a massive elevated area formed by jagged limestone rock that has succumbed to the pressure of tectonic plates, marked by the great incisions of canyons, abysses created by sinkholes, and high peaks that reach 3,700 meters.

One sector of the Eastern Sierra Madre, the one that I am proud to call home and work to protect, is the Sierra Gorda. As its name indicates, the Sierra Gorda is generous and opulent (“gorda” means “fat,” or “opulent” in Spanish). It boasts a variety of flora and fauna that few mountainous regions can claim, ranging from Neotropical species, dependent upon hot climates, and Nearctic species that arrived from the north during glacial periods over the course of millions of years. This mountainous corner in the northern third of Querétaro State truly hosts the best of the Americas.

Ecosystem diversity

The Sierra is populated by Douglas firs on its highest peaks and guanacaste and ceiba in its deep valleys and steep canyons, tree ferns in its wettest reaches and endemic species in the semi-desert. Without a doubt, nature has been generous here: 2,308 plant, 343 bird, 110 mammal, 134 reptile and amphibian species have been documented here, as well as 800 species of butterflies, a third of all butterfly species found in Mexico.

A margay, a crystal butterfly and a bromeliad lizard, wildlife in the same cloud forest.

Snowfall in the highlands, where very mexican agaves and Douglas firs live together.

An arid garden to the west

From the highlands, a window to the sunset.

The gentle hills of the Extoraz river basin are heaven for cacti. A Querétaro peyote and a rare horny toad, inhabitants of the desert.

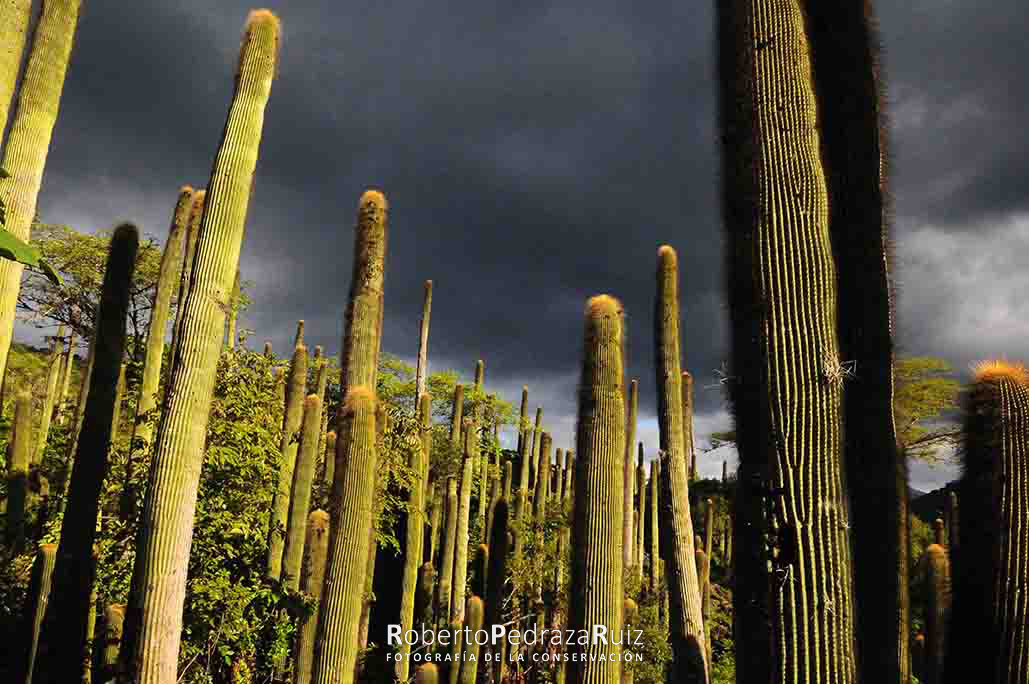

The majority of visitors to the Sierra Gorda arrive from the west and are first welcomed to the area by the ancient semi-desert, which has occupied the low hills of the Extoraz River watershed for 50 million years. This region boasts an impressive array of cacti and other plants adapted to arid conditions, and the millions-of-years stability of the landscape has allowed for the evolution of numerous endemic species, including the golden barrel cactus, the Querétaro peyote, the golf-ball cactus, and the Querétaro yucca. Unfortunately, many of these endemic species are threatened by illegal collecting. The golf-ball cactus, as well as the Querétaro yucca, considered the most beautiful member of its family, are extremely endangered and nearing extinction. Illegal harvesting of the Querétaro peyote is tragically carried out under the mistaken belief that the plant has the same hallucinogenic compounds as its close cousin, used by the Huichols in ceremonies.

Higher-up in the Sierra, pinyon pine forests are adorned for a few weeks each year with the golden explosion of millions of wild cempasuchile flowers.

A pair of endemic Querétaro yuccas in a high ridge among Pinyon pines.

Forests of the high country

As the Sierra continues rising, a dense, green cover of conifers and oaks begins to dominate the landscape. On the highest peaks (reaching 3,160 meters), Douglas firs, true firs, pines, cedars, junipers, and yews form ancient communities. Coexisting in certain areas with 34 different species of oaks, from shrubs to grand trees whose trunks reach 30 meters in height and 1.5 meters in diameter, they create mixed forests. This habitat for bobcats, pumas, hawks, mountain trogons, and flying squirrels that nest in tree cavities is abundant in the sounds and smells of coniferous forests.

Mexico has the greatest variety of pine species in the world. Eight species grow in Sierra Gorda.

A male mountain trogon in its nest.

In the past, military macaws nested in many of these high peaks and steep valleys. Today, in most parts of the Sierra Gorda, one can find only a memory of them in local toponymy. The last surviving colony of military macaws remains in two small refuges, trying to hold on against the advance of humans.

Sierra Gorda harbors the last colony of military macaws in central Mexico.

It is up on those peaks that, during cold fronts in winter, one can witness seas of clouds, dazzling white sunrises, and trees covered in frost reflecting the sun’s first rays. Sadly, these magnificent landscapes are becoming increasingly rare due to the rising temperatures associated with climate change. The warmer climate has also resulted in a plague of tree pests that is diminishing the health of the Sierra Gorda forests. Vital for our wellbeing, these forests occupy the uppermost reaches of the area’s watersheds. As they receive rainfall, they replenish the groundwater that feeds the region’s principal rivers, including the Extóraz, Escanela, Ayutla, and the Concá, which all flow into the great Pánuco River on its way to the Gulf of Mexico.

Tree trunks shining with their own light

In the intermountain valleys that extend over the low zones of the Sierra Gorda, in the deep canyons of the Santa María and Moctezuma Rivers, the flora of the tropics reign. Here leguminous species dominate the forest canopy, strangler figs choke out other trees and cling to rocks, and gumbo limbo trees shine from their brilliant, smooth bark.

Deep canyons and extensive forest are vital corridors for large predators like jaguars and pumas.

In areas dominated by limestone outcroppings and cliffs, organ cacti form unique colonies. They stand erect and parallel to one another, opening their flowers only at night to seek pollination from nectarivorous bats. During the dry season, the trees of the dry tropical forests stand leafless, holding their breath and withstanding scorching heat while thousands of cicadas celebrate their brief life above ground with a droning annual chorus. When the rains finally arrive, timid greens begin to color the forest canopy and, within a few weeks, take over and turn everything a vibrant color. The trees are perfectly adapted to this annual cycle.

Towering cacti, a serrated casquehead iguana, and a ferruginous-pygmy owl, species of the dry tropical forest.

Gumbo limbo trees and their gorgeous bark and colors.

A kinkajou resting in the forest canopy.

The veins of the Sierra

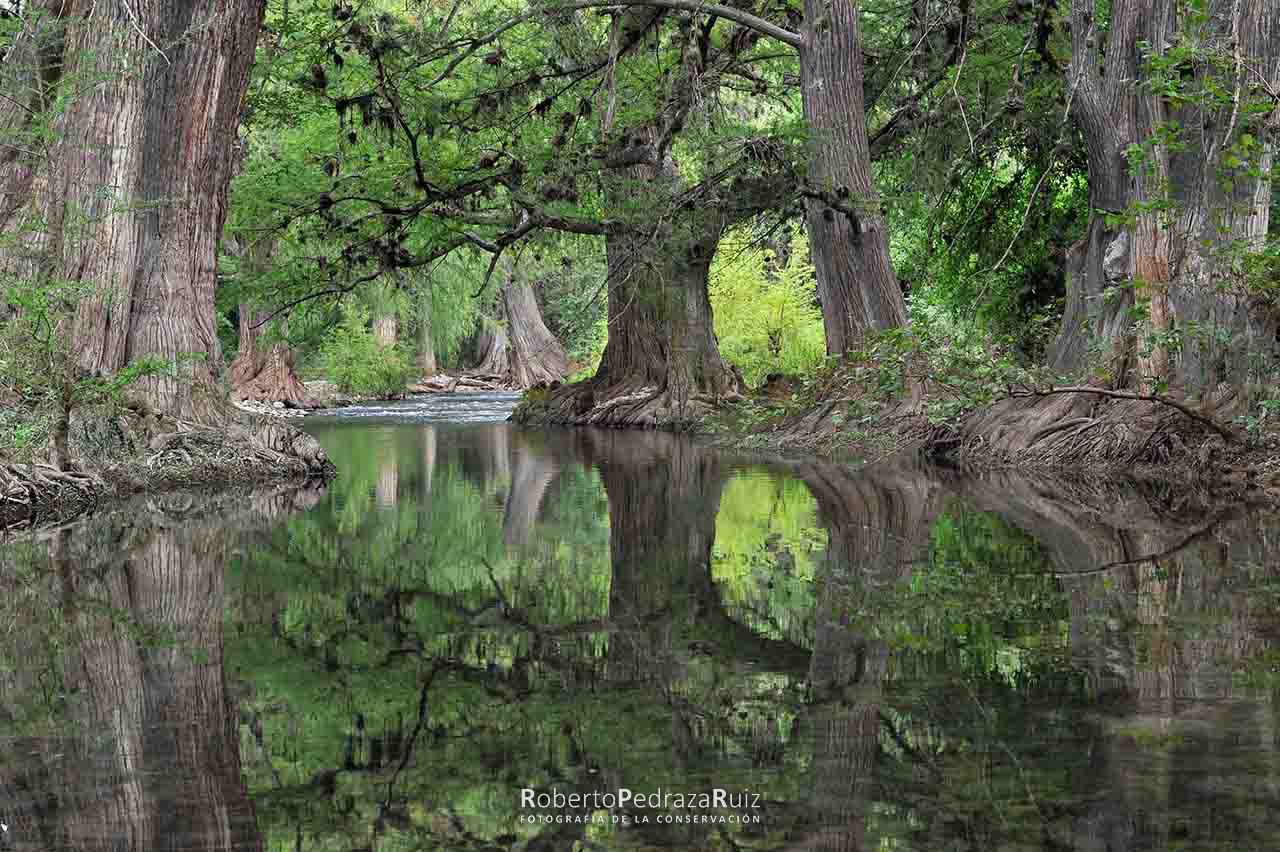

The principal waterways of the Sierra begin as trickling streams in the high altitudes and flow cold and clear, gathering volume as they descend.

In a few stretches of these high mountain streams, well protected by overhanging conifers and oaks, one of Mexico´s axolotl species (Ambystoma velasci) survives. These salamanders are incredible amphibians that pass the majority of their lives in an embryonic stage and are an indicator species for stream health because of their preference for uncontaminated water.

A mighty axolotl bull.

Further downstream, corpulent cypresses, elegant sycamores, and slender willows populate gallery forests and, with their roots, support river banks, slow down water, and enable the existence of 27 species of fish as well as several endemic species of crayfish. At night, these forests fill with the special sound and rhythm of frog choruses.

Old growth Montezuma cypresses growing along the Jalpan river, sycamore leaves in the fall, and a toad couple working to bring in a new generation.

When seen from above, the intimidating ridges extending toward the east from the Moctezuma River to the Santa María River look like a winding path that leads to the Huasteca region. They have retained most of their forest cover, with forest types ranging from dry tropical to temperate and cloud forest. Cloud forests are the preferred habitat of the threatened great curassows, the endemic bearded-wood partridges, and six feline species (representing all the cats found in Mexico), including the powerful jaguar, the puma, and the margay.

Where clouds reign

On the steep slopes, in the ravines and valleys that stand in the path of moist air and clouds originating in the Gulf of Mexico, one can find my favorite ecosystem: cloud forests. Although they cover less than 1% of Mexico’s territory, they have more biological diversity per surface area than any other ecosystem in the country.

A tiny Hygrocibe mushroom among the moss in the cloud forest.

These moist environments provide a habitat for a variety of species, ranging from rattlesnakes to proud oaks, cedars and sweetgums. Mosses, ferns, bromeliads, orchids and even cacti use the trees as living perches, creating complex communities in the forest canopy where the apex predators are tree salamanders and frogs.

An ancient oak, its majestic crown laden with mosses, bromeliads, orchids, ferns and even cacti.

A white-crowned parrot and an owl butterfly, both dependent on healthy forests.

In this ecosystem, new species are still waiting to be discovered. When I photographed two magnolias and shared the images with the British project ARKive, a botanist from Guadalajara saw the unusual trees and began an investigation. Months later, one of the two new species was described and named in honor of Dr. Jerzy Rzedowski, Mexico’s preeminent botanist. The other became part of my family when it was baptized in my honor as Magnolia pedrazae. This is a true privilege and a source of great satisfaction for a conservationist and nature photographer. Magnolias are unique: they are the first flowering plants on the planet and so represent authentic living fossils.

Bromeliads, salamanders, and porcupines depend on the health of these forests, as do we.

Lemboglossum rossii, an endangered orchid that inhabits cloud forests, is now protected in one of the private reserves that we manage.

It is our misfortune to live in the Anthropocene and to witness the most destructive wave of mass extinction that life on our planet has ever encountered. While the human population and demand for resources continues to grow exponentially, 50% of the world’s biodiversity may be eradicated by 2100. Either we act now, or future generations will inhabit on a very different planet, one without many of its ecosystems and most of its species already gone or on the edge of extinction.

I hope that my photography does not just document the exquisite biodiversity we still have, but that it also serves as an effective tool for its conservation.

A pair of male bumble-bee hummingbirds, the second smallest bird in the world and endemic to Mexico.